Japanese admiral Yamamoto downed by long-range Lightning strike

A MESSAGE intercepted 75 years ago began the US mission to shoot down Imperial Japanese Navy commander Isoroku Yamamoto.

A Lockheed P-38 Lightning twin-engine fighter, which was used during World War II, flies over Los Angeles in 1940.

Today in History

Don’t miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

AS US Military Intelligence Service linguist Sergeant Tarno Harold Fudenna translated a radio message that would bring down Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the Fudenna family were held as enemy aliens back in Utah.

Fudenna had been transferred to New Guinea from a brief stint at Camp Chelmer on the Brisbane River when Allied Fleet Radio Units (FRU) in Melbourne and Hawaii intercepted the Japanese Navy transmission.

Fudenna, a nisei or second generation Japanese American, later explained he was called on to translate one of a flurry of messages that followed the transmission 75 years ago of message NTF131755, sent to Japanese commanders of Base Unit No 1 and 11th and 26th Air Flotillas.

Intercepted on April 13, 1943, the message was transmitted in Japanese Naval Cipher JN-25D, already deciphered by Allied intelligence. The transmission details of Yamamoto’s plans to visit to the Solomon Islands days later surprised American commanders.

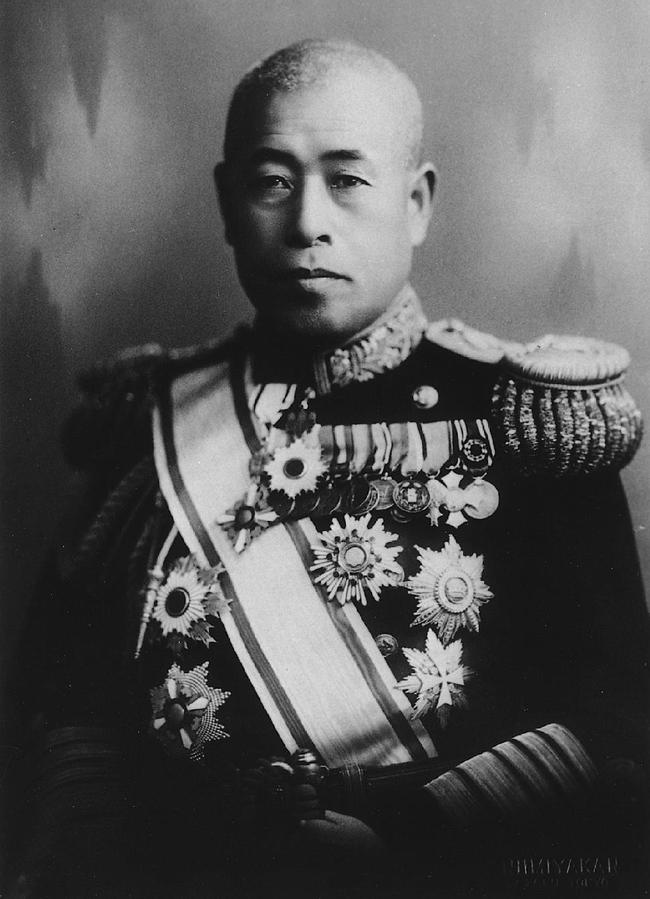

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto.

The intercept revealed Yamamoto would depart “RR” Rabaul at 0600 in a medium attack plane (G4M1 Betty) and land at “RXZ” Ballale Airfield (Solomons) at 0800, proceed by subchaser to “RXE” Shortland at 0840, depart at 0945 and return to Ballale at 1030, depart at 1100 aboard G4M1 Betty and arrive at Buin Airfield (Kahili, Bougainville) at 1110. At 1400 depart “RXP” Buin by G4M1 Betty and arrive back at Rabaul at 1540.

Yamamoto planned to inspect Japanese air units participating in Operation I-Go that began on April 7, 1943, and also boost Japanese morale after their disastrous campaign at Guadalcanal. In 1919 the Japanese navy sent Yamamoto to the US to study language at Harvard University, and in the 1920s he was a Japanese Naval attache in Washington DC. He respected and admired the American government and its people, and opposed Japanese plans to go to war. After failing to convince Japanese leaders that an attack on America would lead to a prolonged war of attrition that Japan could not hope to win, as commander of the Imperial Japanese Navy Yamamoto oversaw the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941.

Tighnabruaich, Indooroopilly, Queensland, in 1991.

Success in the Dutch Indies, Burma and other Japanese victories under Yamamoto, enhanced by his understanding of US military tactics, made him a key American target. When Allies intercepted Yamamoto’s itinery for April 18, secret plans began under Operation Vengeance to intercept and shoot him down.

Since July 1941 the US military had recruited Japanese speaking nisei for intelligence forces, although they were not initially given access to high-security intercepts. Many Japanese-American families, including the Fudennas who were evacuated from their vegetable farm at Warm Springs in Washington State in 1942 and interred at Utah until the end of the war, were detained.

American pilots from the Operation Vengeance mission to shoot down Admiral Yamamoto, April 1943.

Nisei personnel arrived in Brisbane from July 1942 to join the Allied Translator and Interpreter Section at Indooroopilly Racetrack, and later camped at Camp Chelmer on Rosebery Terrace, Chelmer. They joined the interrogation of Japanese POW’s at Tighnabruaich mansion at Indooroopilly, where POWs were held in adjacent cells, and helped translate 70 enemy publications. Fudenna, who transferred from Brisbane to 138th Signal Radio Intercept Company at Seven Mile Strip, New Guinea, with the Fifth air force in January 1943, was one of many nisei to claim a direct role in Operation Vengeance, although his involvement has been questioned.

US Admiral Chester Nimitz oversaw Operation Vengeance, where 16 P-38 Lightnings, equipped with long-range fuel tanks, from the US air force 339th fighter squadron flew 700km from Guadalcanal, at 20m over open sea to avoid radar and Japanese coastwatchers.

Camera-gun photograph of a Japanese ‘Betty’ bomber, taken in June/July 1943 during the 58th Japanese air raid on Darwin.

Japanese fighters took off near Rabaul before dawn on April 18, and flew southeast for a scheduled landing at 8am at Ballale. The weather was described as fine with intermittent cumulus clouds.

Accepted as a “needle in a haystack” mission, the Lightnings flew by compass in radio silence. Expecting only five to 10 minutes in the target zone, their chance of sighting Yamamoto was estimated at 1000-to-1, even before Japan’s Bougainville base potentially launched 75 Zeros in attack.

If the Americans arrived too early, they would be detected and shot down by a swarm of Zeroes. Too late, and Yamamoto would have landed and been taken to a safe bunker. Yamamoto was known to be fanatical about punctuality, so his transport Betty bomber T1-323, another bomber carrying Yamamoto and an escort of Zeroes arrived on time. The Lightnings had been there about 60 seconds, and swooped. Yamamoto’s bomber was attacked around 9.30am by P-38G Miss Virginia, piloted by Rex Barber, and crashed into the jungle on southern Bougainville. Although Barber’s plane was riddled with bullet, he made it back to Guadalcanal.

0 comments